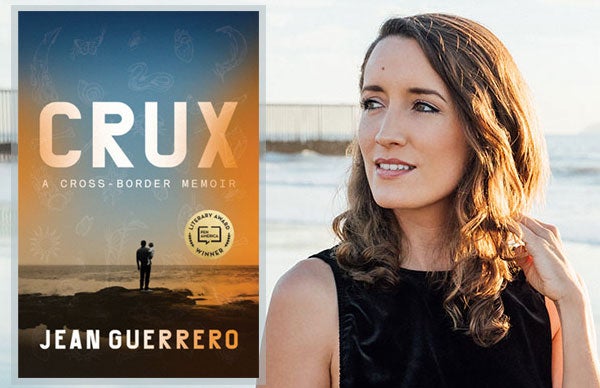

Jean Guerrero is a writer and journalist with extensive experience reporting in Latin America as a foreign correspondent. In her memoir, Crux, Guerrero describes her quest to understand the mind of her father, an immigrant from Mexico who she grew up believing was schizophrenic. We talked to Guerrero about her unique writing process, border politics, and what messages she’s hoping to send to her audiences.

Can you talk about how you applied journalistic methods to writing an autobiography?

Writing Crux entailed filing Freedom of Information Act requests, scouring microfilm records from the early 1900s, traveling through Mexico to retrace my ancestors’ footsteps, hunting for documents in my family members’ garages and closets, and conducting hundreds of hours of interviews.

One of the most helpful resources were the dozens of VHS tapes my father had filmed during my childhood and while my mother was pregnant with me. By watching those videos and taking notes, I was able to recreate scenes from before I was born. They helped me get insights into a happy period in my parents’ relationship that I wouldn’t have had otherwise—moments of tenderness and love that they do not recall.

What was your process like for this book? Do you have any advice for writers exploring their own past?

In Crux, I was trying to solve a real mystery: my father. One of the biggest challenges was separating what I wanted to believe from what I actually believed; the whole process was so emotional and there was a lot to untangle. The advice I would give to other writers exploring their pasts is the same advice that I got from my mentor Suzannah Lessard: learn to be comfortable with uncertainty. You don’t have to have all the answers. The beauty of memoir is its ability to capture the multi-layered, in-flux nature of reality. If you try to have a simple, single answer, you will fail the reader.

The most difficult thing about writing Crux was how naked I had to become. Even when I thought I had stripped myself bare, when I felt raw and exposed, I found that if I questioned myself—is this really the deepest layer?—there was almost always a deeper one below that. Real, honest transparency came only when I admitted that there were things I didn’t know.

You spent much of the book navigating the American border, before the election of President Trump. What differences have you noticed on both sides of the border since then?

I started covering the US/MX border under the Obama administration, which was deporting record numbers of people who were in the country illegally. Under Trump, the immigration crackdown has shifted towards legal immigrants, including asylum seekers who are fleeing horrific violence in Central America.

Another shift I’ve noticed is the public’s response to US/MX border realities. There has been a lot of outrage about the Trump administration’s family separation practice, which I was covering months before it captured national attention. But there was little outrage about record deportations under Obama. I think part of the apathy about Obama’s deportations, which were also a form of family separation, was because they focused on men who were accused of committing crimes. Mainstream America has a hard time sympathizing with dark-complexioned men with criminal records, even if those crimes are misdemeanors like DUI’s.

In the book, you address your father’s struggle with mental illness and substance abuse. You write, “I have found no medical records corroborating the diagnosis of ‘Schizophrenia’ that my mother cited when I was a child. But it is not accurate to call him a ‘Shaman,” either. Each label is reductionistic in his case. They blind me to the complexity of his reality and my own. North of the border, Papi might be diagnosed, medicated.” You also mentioned that you authored a weekly column exploring the link between spirituality and science. Can you talk more about this supposed dichotomy?

I know there is not a hard dichotomy. There is magic in the United States, just as there are pharmaceuticals in Mexico. But one thing that is true is that Mexicans are much more comfortable generally with the idea of reality as this porous fabric with spirits on the other side. Death and the deceased are a central aspect of the mainstream culture.

While I was growing up in the U.S. I had a tendency to view my father through a purely diagnostic lens: I believed there was something wrong with the neurotransmitters in his brain. In Mexico City, I met distant relatives who believed my father was a healer with shamanic powers. I laughed at the idea until I discovered that my father did in fact have a great grandmother who was known for communing with spirits and healing people. Around this time, he created a garden of curative crops. His kitchen filled with homemade powders and potions. I couldn’t ignore the parallels.

Ultimately what I concluded is that the U.S. and Mexico have a lot to offer each other in terms of perspective; the more porous the border when it comes to the exchange of ideas, the richer our understanding. Journalism is always more true when it acknowledges the mysteries that remain.

Which audiences are you looking forward to talking to the most for your speaking engagements? Are there any messages you hope you can send?

I am looking forward to reaching people who, like me and my father, have spent their lives navigating borders, but also the people who have rigid ways of thinking due to growing up with fear.

In my book, the border is as an opportunity to advocate for curiosity. It’s more than just a line on a map or a fence in the sand. It’s a metaphor for moving beyond the familiar, beyond our echo chambers, beyond the known into the unknown. In Crux, the border is a bridge between worlds, be they the worlds between daughters and fathers or the worlds between countries.

Contact us to learn more about bringing Jean Guerrero to your next event.